And if I wake from Dreams

Shall I fall in Pastures

Will I Wake the Darkness

Shall we Torch the Earth?

– “Fall Apart” by Death In June

The following is a brief introduction to a Finnish politician of the Cold War era, who was known for his unusual experience during the Finnish Civil War, his esoteric theosophical worldview, and his commitment to pacifism. The biography below hopes to present a part of Northeastern European history that despite its peculiar story embodied rather common transnational themes of 20th century spiritualism and war.

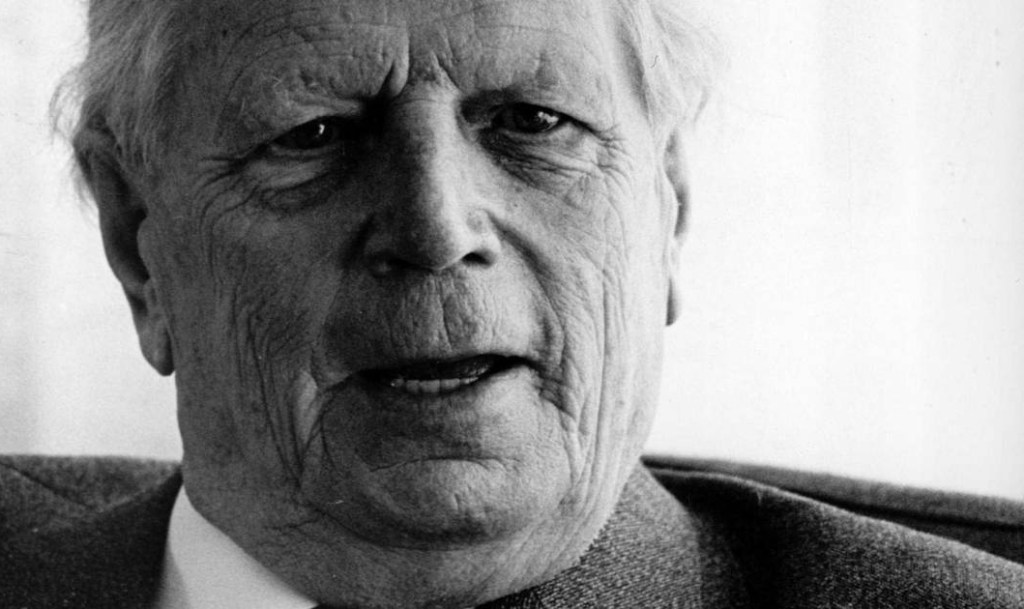

A 1971 interview with a former Finnish Minister of Defence, Yrjö Kallinen (1886 – 1976), kicks off with a question on how the tense global affairs, the state of a world in a ‘cold’ conflict, will unravel. Then already an old man goes on to ramble about the grim looking situation looming over Europe and the world – ever advancing militarization and the threat of yet another global war. What becomes immediately clear from the very first minutes of the interview is that Kallinen is an enigmatic speaker, enthusiastically practicing his assertive voice for dramatizing pitches and expressive intonations. Notably, he quickly gives a profoundly learned image of himself, quoting Einstein and Russel with great appraisals of their names. The general message is that if we don’t change the way we think, we will walk towards an inevitable planetary annihilation, referring to a timely worry expressed by Einstein. Whether a prophecy or merely an assessment, behind this impactful orator stands intriguing pillars of Northeastern European history, to which we will briefly dive in below.

This Ministry of Defense was a staunch a pacifist, holding great responsibility in the protection of a nation situated in a challenging part of Europe, vertically sandwiched between Scandinavia and the Soviet Russia. However, his anti-war values and pacifist practices were seemingly not so much molded in the mid-century hellfire, as they were already tried and tested during the Finnish Civil War (1918). Independent Finland, while managing to separate from its former overlord as the Russian Civil War swooped like a wave across Eurasia, succumbed into its own Civil War between ‘the Whites’ and the ‘Reds’ less than two months from the declaration of independence. During this post-independence storm, Kallinen, man of a simple but accomplished proletarian background, remained a pacifist while mediating between the two militant establishments.

Yet his anti-war stance is not the most peculiar part about him. Kallinen was called a “living paradox” by his contemporaries. As a young socialist in the Civil War, he had faced four death sentences, yet lived till the age of 90. His education was limited to elementary school, but what was lacking in his formal education was compensated by his thorough self-study to a well-educated level, being later officially commemorated as an intellectual. Despite his socialist background he was also a well-known theosophist, an ardent student of mysticism and Eastern religions. Perhaps calling Kallinen a ‘paradox’ does not do justice to his character, which in its multi-faceted nature made him even more of an anomaly than it seems at first glance.

Ihmiset voisivat elää rauhaa – mutta eivät voi, koska heidät lapsesta saakka kasvatetaan kilpailemaan ja taistelemaan, voittamaan, kukistamaan, alistamaan ja tappamaan toisiaan. Tämä kasvatus ja siihen pohjaava elämänkäsitys todellistaa itsensä: Syntyy ja säilyy asiaintila, jossa on kilpailtava, taisteltava ja tapettava.

People could live in peace – but they are unable, for they are since their childhoods raised to compete and fight, to win, defeat, oppress and kill one another. This upbringing and the understanding of life based on it realizes itself: A scenario is born, in which one must compete, fight and kill.1

The rise of theosophy among the educated in Northern Europe is an intriguing thing. In Finland, the 19th century spiritualism was particularly concentrated on middle- and upper-class circles, but found its way into some networks of the labour movement at the beginning of the next century. The Finnish Theosophical Society, which represented one strand of esoteric thought, was established in the still Grand Duchy of Finland in 1907, a bit over 30 years after the founding of the international Theosophical Society in New York. This loosely consolidate New Age school of thought, founded by Ukrainian-born esotericist H.P Balatsky, combines Western mysticism with inspirations from South Asian religions and spiritualism. Theosophist movements were not completely unlikely companions to socialist-adjacent thought, as the affinity with Eastern mysticism and rather direct links to India also motivated anti-colonialism.2

Taken more generally, theosophy could be argued to be a sort of modern day Gnosticism. Personal exploration of hidden or less hidden truths through experience is seen as fundamental for enlightening oneself. Often the ‘answer,’ rather felt than pronounced, included some greater mystical understanding of unity and interconnectedesness. This esoteric quest was also actively present in Kallinen’s life. Reading his musings, such as in the collection Sanat Kuin Valo (which is quoted in this article), and listening to his words like those uttered in the interview, it is clear that these themes were important part of his worldview.

I. Every person a mystery

It does not seem like Kallinen’s interest in theosophy was so much for a timely trend, rather than from a something that had occupied his mind since childhood. He tells that as a mere 4-5 year he was “while sleeping often aware of being in a dream.”, continuing:

“So I once dreamed of playing with other children in our yard. I again, everything being a dream, and wanted to wake up, suggested waking up to others, and yelled: ‘Hey, come to the gates to wake up!’ I rand up to the gates, jumped and romped about until I woke up in my bed.”

According to the author and biographer Matti Salminen, this reoccurring story in Kallinen’s texts is interesting due to seemingly explaining something about the nature of this man – that the basic facets of his worldview, such as ardent pacifism and constant illusion, were developed early, but that he for most of his life sought to find increasingly scientific explanations to support them. It is thus no wonder that the theosophical elements in his thinking transformed into Jungian thought in the later part of his life.3

Maybe, ironically or not, it is due to this search for explanations that pushed Kallinen towards theosophy when he was still under twenty years old, as it stroke him like a flash of lightning. In an interview in 1969, Kallinen recounts that exact moment:

“I saw a man who was walking by, dressed in a work uniform… I looked at him in the eyes and suddenly I saw in front of me a mystery, an infinite miracle beyond words. This experience never withered away. I only have to be quiet for a moment, and a person in front of me will turn into a godly mystery. That knowledge stays within me. I have seen it once, and I can see it again at any moment.” 2

This transformative experience formed into a passion that ultimately brought Kallinen to take part in setting up the local theosophical organsiation in his home city in 1912.

At the beginning of the Civil War, Kallinen was mere a railroad worker in Oulu. According to his account, few details of the recently imploded civil conflict reached this northern town. Kallinen did not consider the essence of the war to be merely the “proletarian revolution” of the Reds, rather, as he recalls: “[people] forget that the whole Finland was making a revolution.”4 Finland had declared itself independent from the Czarist Russia, an independence confirmed by Lenin. Consequently, the institutional order of the state – the police, for instance – had lost its legitimacy amidst the changing of powers. This was also reflected in Oulu, where the leaders of the local labour movement, guided by the governor, selected observers from their organisation to be sent to the law enforcement as a way to increase the institution’s legitimacy. Kallinen was selected as one of such policing actors.

Despite somewhat volatile situation in Oulu, the city was not taken over by the local Red Guard, though they were present. For this reason the Whites were eager to attack the city, but according to Kallinen’s own account, he initially managed to persuade them to stay away while also making the Red Guard abandon their weapons. He was now a mediating actor between the Whites and the Reds – at least until the second round of negotiations, as the Whites attacked anyhow. Supposedly this was partly due to internal miscommunication amidst the Whites – Mannerheim had been informed that Oulu was “liberated from the Reds”, which he had then communicated with the press.5 As it turned out that Oulu had in fact remained as it was and no military operation had taken place, he ordered a swift invasion to make it so. Thus the war came to Oulu, and rather personally so to Kallinen., who was soon convicted for multiple cases, the most puzzling one being “unable to maintain peace despite capable of doing so.”

Kallinen would soon face multiple death sentences, which he received during his prison time while the “national tribunal” was still processing the cases. The White Guard applied Russian Imperial-era martial law to set up court-martial tribunals and enforce respective criminal law, which too was inherited from the Russian military. Fortunately for Kallinen, his reputation in Oulu had at least saved him from field execution. The accusations were mostly concerning varieties of treason. One death sentence came from as he was blackmailed for concealing information about supposed Red Guard weapon stashes, which Kallinen himself recalls as a sham, having no information of such operation. The fourth death sentence was given by the tribunal – in which he was, according to his own account, ‘accused of everything but sodomy.’ 6 Addresses defending Kallinen’s innocence were written by multiple groups, including railroad laborers and theosophists. These defending arguments were not necessarily disputed, rather the narrative given by the accusers were one of a good man gone into ruin.

What followed was a four-years of prison time, that would prove to be an enlightening experience. As part of several revelations, he tells: “Books had said that true freedom is not one bit dependent of restrictions or their absence set up by other people. I had believed it, but not understood. I learned to understand [it].” It was not only the realization of inner freedom that became apparent to him in a rather typical fashion for a spiritual vagabond. He also seems to have reached a more metaphysical self-realization:

“Books have largely described different planes, in which every being create their own world, giving themselves form and spirit, and on which the contents of the soul project to be externally observed. It was as if the curtain was pulled up as I realized this world we inhabit and view to be just like that.”7 .

In 1919 he was finally offered pardon (indirectly with the help of a minister and the president, who were apparently familiar with Kallinen through their wives), which he rejected – he despised the idea of such a priviliged special pardon. Ultimately, after four years of prison time, Kallinen was released as part of a general pardon in 1921.

Our contemporary world may still find relevance, contradictory or otherwise, in Kallinen’s thoughts, most likely to the same degree as previous generations. The idea of nations obliviously walking into their dooms was particularly explored in the last decade in the context of the First World War. Christopher Clark’s widely discussed The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2012) explores the chaotic, often not particularly aware, chain of actions by a variety of actors across multiple countries that ultimately lead to the Great War. The war was not inevitable, just as the Cold War period was not somehow destined to end in a thermonuclear hellfire, despite all the ominous signs Kallinen too was aware of. The fog that clouds the battlefields may as well obstruct the sight of politics and diplomacy – just like in those revolutionary events that kicked off upon the conclusion of the First World War. Perhaps one may sleepwalk to a myriad of fates.

II. Dream and death

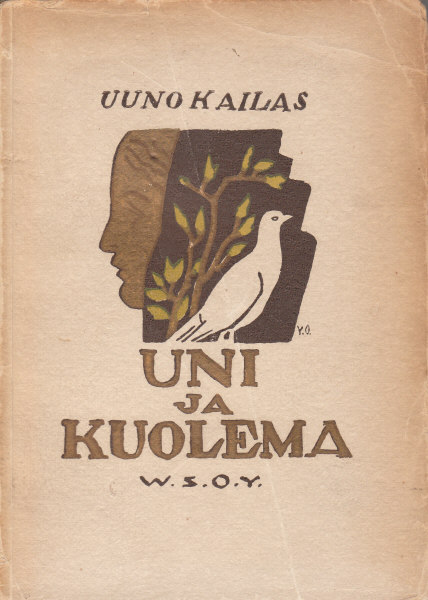

Whether this deep sleep of humankind is dressed in gnostic terminology or international pacifism, in terms of literary aesthetics some may also be reminded of other examples. To mention a certain contemporary, we may consider the Finnish poet Uuno Kailas and his work “Dream and death” (Uni ja kuolema). Kailas’ work was rather expressionistic and personal in nature, though tingled with esoteric atmosphere. One could interpret his nostalgic poem Uni (dream) to be one lamenting the need to wake up, rather the state of being asleep.8 What seems to be a tribute to his mother and his childhood, ends in a mourning realization that “both are dead,” wondering why he “ever stopped dreaming.” It is indeed a personal work, but widely different in spirit to Kallinen’s experience where the consistent mission, also personal in nature, was to abandon the nocturnal world. The dichotomy between these two characters is particularly reflected in Kailas’ personal history – rather than being a workers’ personality like Kallinen, he had joined the Finnish nationalist Aunus Expedition of 1919, an “undeclared” military campaign to occupy certain parts of Eastern Karelia.

Considering that Kallinen was already imprisoned in 1919, there is a poetic duality to the story. The somewhat superficial experiential division between the labor’s “Reds” and the nationalists’ “Whites” – these are first and foremost political divisions – regardless of how meaningful or rooted in reality, could in this story also be expressed as imprisonment and invasion – a commonplace decor on the stage of post-Imperial Europe.

It is tempting to go on a short detour and elaborate on this comparison a bit further. An order by the Grand Marshall of the Whites C. G. E. Mannerheim, also known as the “Sword Oath” (Miekkavala) read: “I will not sheath my sword before all fortresses are in our hands, before the last of Lenin’s fighters and hooligans are expelled from both Finland and White Karealia.” The “order,” a kind of a verbal manifest, supported nationalist aspirations when the post-Imperial borders were being settled in one way or another. As a comical contrast, Kallinen too swore his own oath in prison:

“I swear that I will never in this world, or in the worlds to come, obey anyone or any authority, commander, government, gods or angels, in anything else but what I see as right or as good as possible.”

The previously referred biographer Salminen sees this as the “key to Kallinen’s whole being,” as the most consistent part of his life – his very nature as a dissident.9 It seems like in this rather simple anti-authoritarian statement lies a clue to the ominous dreamscape. Are we not prone to think that tribalism and ethnonationalism are indeed part of the dream from which he insists to awake from?

Even if Kallinen’s message was more grandiose than the romantic poet’s, directly addressing the state of mankind, the analogies of dream and death may be eerily similar. Whether – and how – to wake up, was the question. In the flurry of political strife and global change, the anxieties of the present crawl up similarly to more personal, intimate landscapes of 20th century dreamy poetics. Abstractions as they may be, those interested in exploring the period’s aesthetics of international relations may find it interesting to not merely study the many furiously chased political aspirations, but more passively experienced dreams and fantasies as well. Regardless, considering many other European works of such thematic, it is curious how this entanglement of dream and death found its way to the first half of the 20th century literary and spiritual consciousness.

All wars are missteps, but Kallinen himself did not judge all war efforts – more specifically, he did approve of Finland’s defensive war against the Soviet invasion (also known as the Winter War). This most likely does not come as a surprise, and not solely because he saw communism as a violent ideology, had found his political home at the Social Democratic Party, and was not all things considered fond of the Soviet system. And yet, it was to a certain extent the Soviet influence that would bring him into the role of a Minister of Defence. Post-war Finland had to tread lightly in both its internal and external politics, both of which were influenced by Soviet interventions from time to time. Kallinen’s appointment as a Minister of Defense would thus attempt to signal the Soviet Union of Finland’s anti-militarism. The paradoxical nature of this appointment was further complicated by the fact that he only agreed to the role on the condition that the actual military affairs would be outsourced to another politician.

III. Staying awake

We have observed that pacifism and esoteric tendencies seemingly never let go of Kallinen’s worldview, despite the wars and collapse of both national and regional orders. However, that is not to say that the stormy conditions of a rapidly changing world completely dictated how these esoteric notions developed. One researcher discussing another spiritualist of the same period noted the importance of observing the momentary dynamic of religion and civil society.10 Relevance of a belief system oscillates between a variety of forms throughout a person’s life. The meaning of more subtle elements in these systems reveal themselves in a practical, operational experiences.

We could thus observe that Kallinen, who found the early 20th century spiritualist thinking that would later capture more philosophical and scientific interests, stayed nonetheless principled in his anti-war stance throughout the most trying times. He seemingly never let go of his views on the sleeping mankind, quite the opposite. There’s no doubt that the societal and even global changes in one of the most devastating periods of human history affected the man’s thinking, but the operationalization of these beliefs seem to indicate that certain more metaphysically oriented ideas remained foundational – the knowledge he supposedly acquired in his youth, one of ever-recallable miracle that is human, seems in hindsight rather convincing as a spiritual foundation. What this in practice may tell us of the interplay between theosophy and socialist perspectives, or the strength of the communities taking part in them, is a question that has been only marginally studied.

What to take away from the story of this particular character is thus not necessarily that war should be avoided at all cost, for that is certainly what most are intuitively aware of. Salminen argued that Kallinen’s main question may not have been so much whether we live in a dream, rather than a twofold fundamental question of “what is life and what is a human.”11 Inspecting his story through the historical lens, we may envision an individual who despite his defiance and at times unwelcome ideology, in some ways embodied the contrasts of Europe that was, through a purgatory of sorts, trying to come to its senses. Increasingly occupied with natural and social sciences, with psychology and sociology, Europe knew of forces that would bring about war and destruction, but could not avoid them.

Considering the above, the theme of this article is not so much a question of human folly and war, but about peace. Our contemporary puzzle now is that understandably – and likely correctly – in the minds of many, a Ukrainian capitulation would bring forth more violence and war. An end to war does not necessarily mean peace in practice, nor an end to hostilities in general. In this sense, whereas we may discuss the nature of a war, in some cases we ought to consider the nature of a peace. This is certainly true for those who study Finnish society before and after the Civil War, particularly in the context of the postwar White Terror, causing further suffering on an already divided nation. Kallinen, a universalist in a shrinking world, did not seem to care of such divide. Ultimately, it is rather clear from his words that for him there were no wars worthy of justification, for all “all wars are holy wars […] every belief that ends in a war is a heresy.”

Kerran koittaa aika, jolloin nääntynyt ihmissuku rikkiammuttuine kulttuureineen ei enää jaksa menettää enempää. Silloin tulee rauha.

There will be a time when the starved mankind with its obliterated cultures does not bear to lose any more. Then there will be peace.

Further reading

- Ala-häivälä, Kai. “Vankina valkoisten : Oulun vankileiri 1918” -pro-gradu tutkielma. Helsingin Yliopisto, 2000.

- Järvenpää, Juuso. Kansan henkinen kehitys. Työväen historian ja perinteen tutkimuksen seura, 2024.

- Kallinen, Yrjö & Harri Markkula (toimit.). Sanat Kuin Valo – Yrjö Kallisen ajatuksia. WSOY, 1995.

- Salminen, Matti. Yrjö Kallisen elämä ja totuus. Into Kustannus, 2014.

Interviews

- Kallinen, Yrjö & Yleisradio. “Sisällissota 1918 – punaiset muistot: Pasifisti Oulun poliisitarkastajana (Yrjö Kallinen, Oulu)” [Audio]. Yle, 1965. https://areena.yle.fi/1-4326628

- Lindfors, Jukka. “Elämmekö unessa.” Yle, 2006. https://yle.fi/a/20-82079

- Salminen, Matti. Viikon tietokirja: Yrjö Kallisen elämä ja totuus. Yle, 2011. https://areena.yle.fi/1-1108044

- Quotes from Sanat Kuin Valo, all translations mine. ↩︎

- Not too long after its establishment, the Theosophical Society split into two organisations, one located in California and the other in India. See also theosophists such as Annie Besant who resided in India and became an active supporter for Indian self-rule. ↩︎

- Matti Salminen, Yrjö Kallisen elämä ja totuus (Into Kustannus, 2014) 37. ↩︎

- Yrjö Kallinen & Yleisradio, Sisällissota 1918 – punaiset muistot: Pasifisti Oulun poliisitarkastajana (Yrjö Kallinen, Oulu). Yle, 2018. ↩︎

- Salminen, Yrjö Kallisen elämä ja totuus, 34. Quoting historian Kustaa Hautala. ↩︎

- “[…] kaikesta muusta paitsi väkisinmakaamisesta.” Salminen, 39. ↩︎

- Ibid. 48-49. ↩︎

- In the poem, the narrator vividly recalls being a child again, and the soothing voice and touch of his mother that would calm him when suffering from a nightmare. In the end, he realizes that “there is no mother, there is no child – both are dead.” Finnish: “Ei, ei ole äitiä, lasta – / kuollut on kumpikin. / Miks lainkaan uneksimasta / havahdin!” ↩︎

- Ibid., 41. ↩︎

- Juuso Järvenpää, Kansan henkinen kehitys (Työväen historian ja perinteen tutkimuksen seura, 2024) 363. ↩︎

- “Yrjö Kallisen elämä ja totuus / Matti Salminen & Hannu Taanila 27.10.2011” https://youtu.be/L24RI1Layds?si=hJZlYI7hqDXnjpns ↩︎

Leave a comment