European sciences, from natural sciences to humanities, developed comprehensively in the 19th century. These advancements were not only linked with socio-economic developments but also with colonialism, imperialism and war within and outside the continent. Natural sciences in particular influenced other studies in this century, both in substance and methodology, expanding taxonomical thinking all the way to fields of study as such as linguistics. One of these linguistic theories where natural sciences, political devices and historical studies conflated into one broader school of ethno-linguistic thought was so-called “Turanism.”

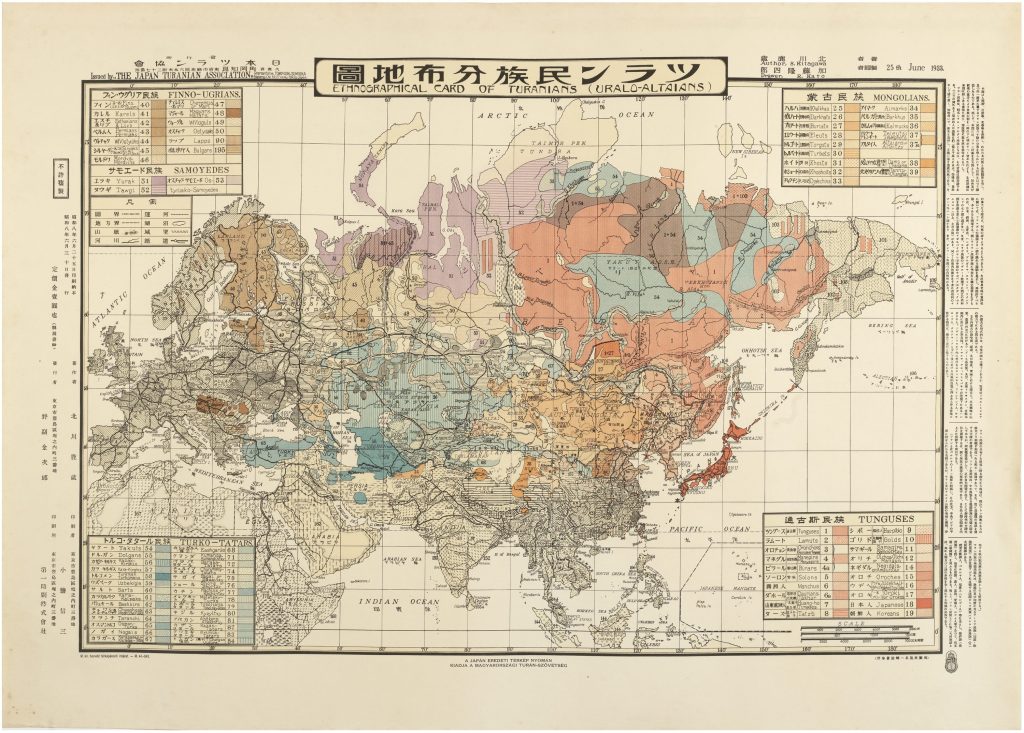

The 19th century Turanism is an elusive theory gaining different meanings and forms through mid-19th till early 20th century, but which at its core was an ethno-linguistic theory embedded in the 1800s’ scientification trends, though its linguistic and ethnological bits and pieces can be traced even further back. At its basic form, it assumed an affinity between several ethnolinguistic groups inhabiting primarily Central-Asia, North Eastern Europe, Siberia and North Eastern Asia – more specifically Turkic, Finnic and Mongol peoples and languages.

As the concept was tied to the 19th century nation-building trends, the idea also expanded into history writing and further into European linguistic studies through works such as those of a German philologist Friedrich Max Müller (1823 – 1900) ultimately covering multitude of Eurasian languages across Eurasia. While the more contemporary term – “Ural-Altaic hypothesis” – is primarily a linguistic one, Turanist and Ural-Altaic theories tended to overlap. The often cited “pioneer” of early ideas in Turanism was a Finnish linguist Matthias Castrén (1813 – 1852). Fitting for his time, Castrén was also a nationalist and a Fennoman – an activist pursuing for an elevated standing of the Finnish language in the Grand Duchy of Finland where the language of the elite was still Swedish. His linguistic project, a great field expedition to find the “origin” of the Finns, should thus be seen in this 19th century nation-building context. After returning from his journey across Siberia, he held a lecture on the origins of the Finns (1849) where he proclaimed his countrymen to have been “Turanians” originally from the Altai Mountains.

One could argue that Max Müller was one of the first ones to really consolidate the Turanic theory into a grander linguistic tradition by blending it into a more rigid scientific taxonomy. Indeed, Müller, a German philologist then located in the UK, was not only aware of Castrén, whom he had even called the “heroic grammarian,” but cited him rather frequently. Müller would position and contrast the Turanic languages to other two major language families, “Aryan” (Indo-European) and Semitic. He saw the historical development of the Turanian linguistic family to be different to that of the others, and it is here where the differentiations go beyond mere linguistic classifications, revealing an ethnological side to the theory building a taxonomy of peoples.

What Müller saw as the first unique trait to the Turanic languages was the agglutinative grammar. Müller explains in his Languages At The Seat Of War (1854), written as a language manual for the British military in the Crimean war, that the other two language families had gone through the “process of handing down a language through centuries without break or loss” which is only possible in societies “whose history runs on in one main stream,” and where culture is contained in well-defined borders.1

This is not the case for ‘nomadic’ Turanians, who have scattered all across Eurasia, and who, according to Müller, never managed to consolidate a lasting civilization. What makes this rather diverse set of languages to stand out then, Müller explains, are the numerals and pronouns that can be traced back to a common source, although still with less ‘tenacity’ than the ‘political languages’ of Europe and Asia – and, most importantly, the agglutination.

The second quality of these languages is their organisation. According to Müller, the most advanced ones of these languages, Hungarian and Finnish, used to be nomadic – conforming to requirements of the nomadic life – but had now risen to a proper level of sedentary organisation and thus become political, approaching to that of the Aryan kind. They are fixed with “literary works of national character,” and are therefore impossible to be altered without political action.2 Turkish, despite Müller’s enthusiasm for this language, he did not consider to be as advanced. In the 19th century philology, the morphological classifications had immense influence in anthropologically defining languages and its speakers.

Zooming out from the wonders of old-timey philology, we may notice some Said’ian elements at play. The agglutinative group, being rather distant to most Europeans and generally dispersed, suggests that it was an unattractive subject for the European philological tradition. Taking note of Said’s Orientalism, we can argue that its unique status was partly due to their political standing – that is, most Turanians had no colonial or other political relevance in the minds of Europeans, but were either conquered peoples or otherwise subjugated. Sure enough, the imagined linguistic community was also geographically and politically somewhat inaccessible for many Europeans. In this sense, the above-mentioned Müller’s book had a double-edged function: not only it could expand the academic and general knowledge of these languages for the enjoyment of both diplomacy and military, but it could also be part of creating this philology which Turanic languages were lacking. In some ways, the Turanic theory, even with its scientific exploration, can be seen as a political project from its very inception, further built by European linguists on Castrén’s foundation.

As Said explains, the process of establishing a philological field was a powerful tool in creating identities and perspectives on different nations. Sometimes this also included racial views, although Müller’s definition of race is convoluted and perhaps not worth going into in this post. Same applies to his views on religion – briefly put Müller’s works, there is a ‘natural connection’ between religion and linguistics. One of his peculiar implementations of Castrén’s mythology (which he seems to quote and cite in his Science of Religion) is that Müller finds the ancient Chinese and Finnish religions “curiously alike,” and considers them to have been part of the same common Turanic religion.

The historicity of this theory became more pronounced especially in the Finnish intellectual circles in the latter half of the 19th century. One example of this phenomenon is a Finnish historian Yrjö Sakari Yrjö-Koskinen (1830 – 1903). Koskinen too was a Fennoman, even Finnicizing his name (from Swedish, being Georg Zacharias Forsman until 1852). His doctoral thesis “on the ancient nature of the Finnic family” (trans.), published in 1862, starts by honouring the late Castrén and acknowledging Müller, accepting most of their work as a foundation for his study, including the ethnographic trichotomy of Aryan, Semitic and Turanian. Yet, Koskinen attempts to go further than his predecessors, trying to find the even more ancient (that is, older than Castrén’s appointed Altai Mountains) home of the “Finnic family,” meaning the very primordial home of the Turanians. Koskinen’s work is quite clunkily written and at times rather esoteric, perhaps not only due to its peculiar historiography.

Already at the very beginning of his dissertation he claims that “the whole Europe was, before the arrival of the Aryans, under some Turanian natives.”3 These natives left little history due to their small populations and primitive nature, and thus, in order to explore their legacy, the book must dwell on a variety of ancient literary sources, sometimes tackling etymology, to depict ancient nations that may or may not have been part of the Finnic family as well as their possible achievements. These include, for instance, Goths, Huns, and with the work of the French-German Assyriologist Julius Oppert, he finds also Assyrians to be part of this distant family. Using a lot of miscellaneous historical texts, word comparisons and at times studies from other scholars, he identifies Turanian nations and their feats in world history.

Despite what now looks like revisionist insanity, and perhaps not with great academic merit even in his time, the philological methodology merging together linguistics, ancient literature and mythology was not unusual for 19th century academia, and at times even required. For example, Castrén would not have conducted his research expeditions through Siberia had he not believed that comparative linguistics could reveal something essential about the past of the Finns. The view of comparative linguistics as an ethnographic tool was almost a requisite to position Finns among Turanians as well as to write history for them. And, as Koskinen concludes, if the nation “wants history for itself, ergo: it has history.” For him, the fact that the Finnish nation indeed wanted its personal history, as seen in these national historical pursuits, was enough to imply that it must have had its own independent past already before the century under Russia.

Castrén’s theory-crafting and Koskinen’s history were not merely “self-orientalising” pseudo-science, but the sort of European nation-building that was somewhat particular to nations feeling pressured in-between larger linguistic and cultural groups. For Finns, as well as to Hungarians, this position lied between Germanic and Slavic nations. However, Finnish nationalists had plenty of tools at their disposal, including limited autonomy in the Russian Empire and relatively open forum for public discourses. After all, a Finnish nationalism in early-mid 1800s didn’t seek independence rather than victory over the dominance of the Swedish language, which happened to be in favour of the Czar’s ambitions to reduce Swedish influence in Finland. Furthermore, it has been argued, for instance by Timo Salminen, that Castrén’s field exploration through Siberia was in fact in-tune with the Russian academic tradition stemming from the 18th century practice of gathering information about different parts of the Empire.

Turanism as a political “pan-ideology” was certainly more pronounced after the turn of the century, perhaps around the time when it started to lose its intellectual prowess. To illustrate this change I would again like to cite Said, according to who, as Orientalism reached the 20th century, there was a shift “from an academic to an instrumental attitude.” This change was coupled with an extension of the Orientalist identity – if for example Müller had belonged in a relatively niche collective of academics, the Orientalist had now become “the representative man of his Western culture.” That is, someone who embodies a link between the Orient and the Occident by asserting the supremacy of the West – a clear extension to the political qualities of a scholar of the 19th century.

This strengthened instrumentality of Turanism is something that developed towards the end of the 1800s, but maybe more so after the turn of the century, as the political turmoil of the First World War had left more room to mobilize the newly formed national identities. In addition, the Great War marked a change in the characteristics of who Said called “adventure-eccentrics” – traveller scholars who, as an example from this essay, would be similar to Castrén – now being replaced with “agent-Orientalists” such as T.E Lawrence. The tradition of roaming intellectual-adventurers was increasingly militarised, becoming more attached to “geopolitical” planning and occurrences. There were perhaps not too many “Turanian” T. E. Lawrences, but the ruins of the First World War spawned (marginal) pan-Turanian movements and initiatives across Eurasia from Hungary and Turkey all the way to Japan. The “scientific” Turanism was now giving away to political mobilization.

What makes Turanism such an interesting theoretical construct is not only its marginality and overall peripheral nature, but also the way it brought together linguistic and historical theories, all tightly embedded in political events and projects of mid- to late-1800s. Rather than building from Greco-Roman history and mythos, as the European 19th century history writing had a tendency to do, it had to look beyond Indo-European sources, ultimately including small and peripheral languages and nations that so far hadn’t had as extensive historiography in Europe.

Bibliography (Incomplete)

(Primary)

- Müller, Max and C.C.J Brunsen. Letters to Chevalier Bunsen on the classification of the Turanian languages. London: A. & G.A. Spottiswoode, 1854.

- Castrén, Matthias. Archaeologica et historica; Universitaria. Edited by Timo Salminen. Helsinki: Finno-Ugrian Society, 2017.

- Koskinen, Yrjö.

o Johtavat Aatteet Ihmiskunnan Historiassa. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1879. o “Onko Suomen kansalla historiaa?” [Does the Finnish nation have history?] In Historiallinen arkisto V. Helsinki: Suomen Historiallinen Seura, 1876: 1-9. - Müller, Max.

o “The Historical Relationship of Ancient Religions and Philosophies.” In Theosophy or Psychological Religion: The Gifford Lectures Delivered before the University of London in 1892, 58–86. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

o The Languages of the Seat of War in the East. With a survey of the three families of language, Semitic, Arian and Turanian. Oxford: Indian Institute, 1855.

- Max Müller, The Languages of the Seat of War in the East. With a survey of the three families of language, Semitic, Arian and Turanian (Oxford: Indian Institute, 1855) 87. ↩︎

- Max Müller, The Languages of the Seat of War in the East 94. ↩︎

- Yrjö Koskinen, Tiedot Suomen-suvun muinaisuudesta – Yliopistollinen väitöskirja (Helsinki, 1862), 9. “[…] käypi jo mielestäni tehdä se todennäköinen päätös, että koko Eurooppa on ennen Arjalaisten tuloa ollut jonkun Turanilaisen alku-väestön hallussa” ↩︎

Leave a comment