First enter the ethereal sounds of post-industrial music – spacey textures of ambient synths and samples. Soon the storming drums make a resounding appearance. Finally appears the protagonist, the acoustic guitar accompanied by a melancholic, often low-toned voice, calmly giving out lyrics that may at first resemble a typical love song. What makes this composition “neofolk” is not exactly any of its individual elements, though the first part certainly plays particularly important part in it, but the emerging totality embracing aesthetics that are often nothing sort of provocative for a new listener.

The point of this short essay is mainly to argue two points: that neofolk’s and its close relatives’, such as martial industrial music’s, modernist aesthetics and ambiguity of motifs makes them relatively unique artistic scenes. Neofolk does this by readjusting the historical reference point of typical folk art from that of a national romantic past to European modernity. Secondly, by partaking in the interpretation of the modernist past, it enters the field shared by the early 20th century avant-garde and futurist movements. It seeks not to analyse the artistic intentions, since (as the reader will soon find out) that is clearly difficult. Instead, I attempt put its thematic in a historical context.

When we talk about neofolk certain things has to be made clear. First, neofolk has never been well defined, and to even call it a single genre of music indicates that the author is either implying or formulating a unifying theme in it. Indeed, to certain extent the author here is doing both – I am making a case about the aesthetics of the genre, and therefore simultaneously forcing my views on the poor reader about what the genre is (and perhaps should be). This leads me to the second point: the musical and thematic diversity of neofolk scene.

To put it very simply, the genre can be divided into two different types of neofolk: the style described above, that has much more to do with experimental post- and martial industrial music than folk; and the increasingly popular style of more folk oriented music. The lyrical themes also follow the division. In the former, the lyrics often connect to the historical (usually European) past and modernity, while the latter is more concerned with folklore and mythology. Although nowadays neofolk is becoming almost synonyms with the latter, I am, personally, of the opinion that the former is what makes neofolk interesting. I am thus not exactly a fan of the latter and this newer neofolk does not concern the topic of this essay. Therefore, I am only focusing on few musical projects – not to prove my point by avoiding the many divergent cases – but because the point I am making concerns the aesthetics and thematic the post-industrial style represents.

When introducing people to the genre, I tend not to start from one of pioneers, Death in June. This musical project from the infamous Douglas Pearce is no stranger for controversies due to flirting with the far-right, mostly Nazi German, topics and aesthetics. The lyrical and visual content of some of his work is (most likely deliberately) provocative, but often over- or misinterpreted – his iconic use of the Totenkopf -symbol is supposedly not a reference to German atrocities but simply to “death.” Regardless, I rarely start with Jérôme Reuter either, or ROME, who has a large discography spanning over ten albums with varying styles and decrees of approachability. His albums cover historical topics such as war, literature and philosophy, sometimes even reaching out from the European thematic chamber, such as in the album about the Bush War, Passage to Rhodesia (2015), or in the album tingling with influence from Eastern philosophy, Hall of Thatch (2018).

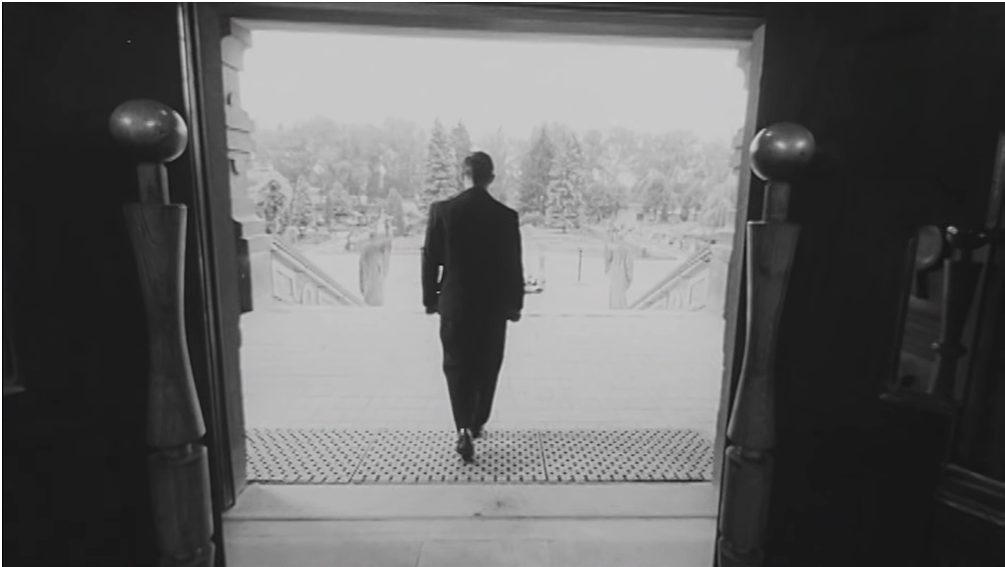

Somewhat surprisingly (and disturbingly for the fans of the genre), I have found the neofolk parody band, Death in Rome, to capture the spirit of the scene extraordinarily well. Death in Rome – name apparently not necessarily a reference to the two pioneers of the genre, but to the novel by Wolfgang Koeppen [1] – use their relatively small Youtube-channel as their main output. [2] Aside from a couple of original songs, they mostly conjure the most insidious, exhilarating and impressive neofolk-covers of well-known pop-songs. But the band is not only about covering Rihanna to the tune of military drumming and melancholic vocals, it is also about the accompanied tongue-in-cheek music video consisting of clips from Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia. [3] The music videos are often more ambitious, but they all share the atmosphere of an intriguing past expressed through black-and-white cult films and historical footage. The devastating footage from the Second World War collide and overlap harmoniously with vintage films from Eastern Europe.

However, the project not only dances across the boundaries of music and visual arts, but also between satire and praise. This is exactly where it manages to capture one of the essential elements of neofolk – ambiguity. I can only quote what was well put in a review by a writer going by the name of Tenebrous Kate, about the satire of Death in Rome: ”Particularly in American culture, where strict categorization is king and ambiguity is suspect, critics tie themselves into knots in an attempt to ascribe motivation to neofolk artists.” Later on, she adds: “Nothing should be taken at face value when discussing neofolk. Beneath the solemn surface, there’s significant room for inversion of meaning and even wry commentary.” [4] It is an excellent description of qualities of such music.

The ambiguity may make it difficult to understand the meaning and the “wry commentary.” It could be, however, that it is not something to be clearly understood as a descriptive commentary, but conceived, with all its sounds and visuals, as an emotional mix of lamentation and enjoyment. What emerges from this mix is something that is sometimes called catharsis. After all, the pursue for catharsis is a popular mission statement in underground music, especially in extreme metal scenes. It may not come as a surprise, then, that when wandering to a ROME-concert, one cannot avoid noticing the abundance of clothing with metal logos worn by fellow gig-goers. To be sure, simply calling it ambiguous and emotionally driven completely lacks explanatory power when it comes to the aesthetics and themes in the music. In addition to being ‘ambiguous’, it surely has to, if not explicitly say, at least show something. And that it does, and this has to do with the concept ingrained in the very term ‘neofolk’.

When it comes to traditional art, or ‘folk’ art, it is often reminded that many facets in social traditions and traditional art are invented. Elements in these inventions include the attempt to establish continuity with a ‘suitable’ past, where a fixed point in history is set to work as a reference and a guiding point for the present. One of the many examples given by Eric Hobsbawm is the rebuilding of the British parliament in 19th century, where Gothic was chosen as the architectural style. [5] Sometimes these traditions do not stem from politically motivated preferences in interpreting history but are transparently created. Very typical example of this, and a relevant one for neofolk, is the symbolism used by the National Socialists in Germany. [6] The historical or a pseudo-primordial point may be, then, moved to a further mark, even to the present, in an attempt to build a future tradition that would look back to the times when they were established.

‘Neo’ in neofolk implies that a break with the past has been reached. What was considered to be folk music is now replaced something new. By listening to Death in June’s or ROME’s music, especially the earlier albums as well as Death in Rome’s covers and observing their visualizations, we may see what their interpretations of the modern traditional might be. Folk songs, depending on the nation and time, often deal with tales, customs and feelings of the past that still successfully present the (supposed) national essence today. Yet, neofolk does not celebrate the past nor the national customs. Instead, it recreates the tradition around a lamenting and grieving perspective where the reference point is fixed to the traumatic period of the European Civil War. The military drumming, samples from historical speeches and the eerie sound space reflect an apocalyptic past that is not to be celebrated nor forgotten, but in its own bombastic way, embraced.

However, the music not only mourns the past, it also seems to imply that in this civilizational apocalypse something very essential was lost. Accordingly, neofolk expresses strong discontent with the modern world. One does not have to look further than ROME’s merchandise decorated with Julius Evola’s famous quote: “Every act of beauty is a revolt against the modern world.” In this observation the inherent contradiction becomes apparent, for one of the feelings evoked from the music is indeed nostalgia. The past is both grieved and missed. This is one of the reasons why many of the projects are found to be provocative – are they not celebrating the most horrible conflicts in human history? Or, even worse, by adopting a lot of the aesthetics from the 20th century fascist movements, flirting with one of the most genocidal regimes the world has ever seen? Death in June, for example, is very much prone to both accusations.

In the face of these accusations, neofolk artists are quick to remind of their apolitical nature. Jérôme Reuter, whose music often sympathizes with historical left-wing movements, said in an interview with Heathen Harvest: “My leaning to the left of things—or whatever it is—is not that important, and I don’t think politics should get in the way of making good art.” [7] Death in Rome’s stance is equally straightforward: “We’re interested in WWII and its aesthetics and nobody may use us for their political purposes. Art is above politics.” [8] Still, Reuter is frank when it comes to the difficulties of declaring art apolitical: “ROME’s songs certainly stand for something. ‘For’, as opposed to ‘against’.” His latest work, Le ceneri di Heliodoro (2019), in which one of the songs has a lyrical passage referring to Enoch Powell’s famous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, makes a rather clear case for its political content, but without disclosing its political direction.

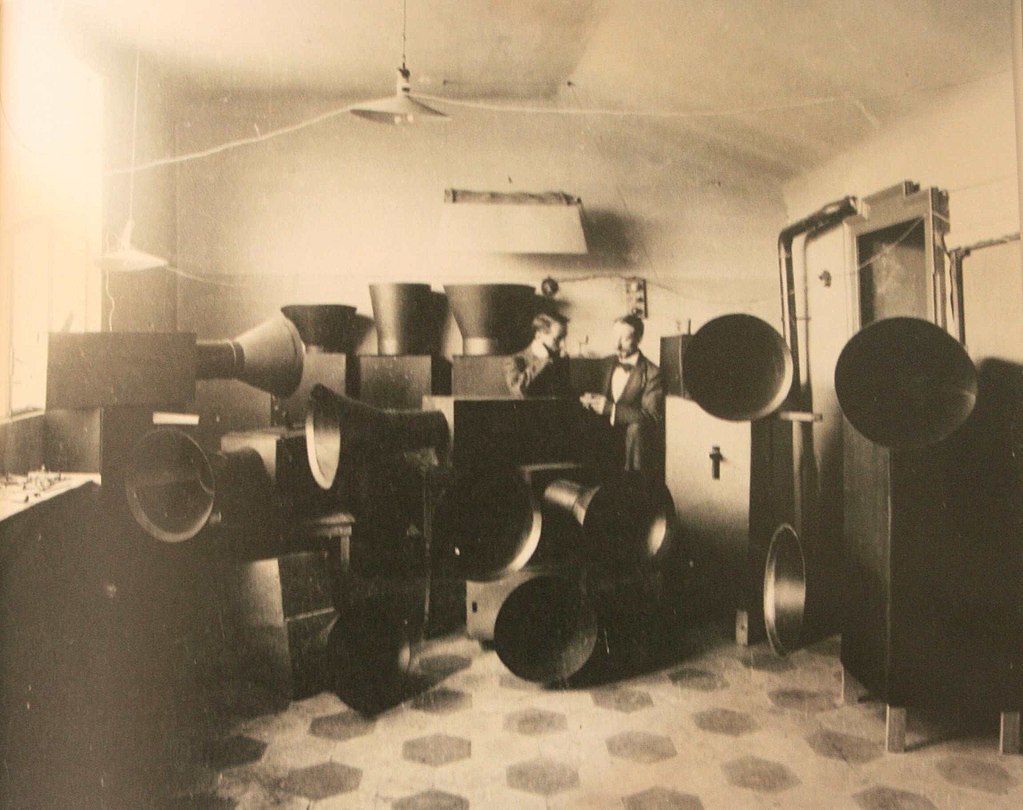

One could see the phrase ‘art over politics’ as either as an excuse for avoiding responsibility for art of controversial nature, or as a way to deny political affiliation with the rather political aesthetics of the art. The latter case is interesting if you juxtapose it against those influential modernist art scenes that emerged before the fixed historical period that is being imitated, especially avant-garde futurism. Filippo Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism (1919) praises war, technology and modernity – the things that would show their might first in 1914 and then in 1939. Although “Mythology and the Mystic Ideal are defeated at last,” this progressive thrust is not waiting for secular or ‘rational’ times nor enlightenment from the pessimism of the late 19th century, as it follows that: “There’s nothing to match the splendor of the sun’s red sword, slashing for the first time through our millennial gloom!’” [9] The millennial gloom is noted already (or, alternatively, still) at the very beginning of the century and, considering that Marinetti was also drafting the Fascist Manifesto in 1919, its climax was to be expected. The similarities in substance between the futurist goals and the neofolk aesthetics are rather evident when looking at the futurists’ celebration for industrial warfare. While I am not supposing that the futurists were waiting for a world war or two, there is certain sense in seeing their artistic inspirations to manifest in the 1940s. Furthermore, the Manifest of Futurism also show similar enthusiasm for contrasts and likeness (“Museums: cemeteries!… Identical, surely, in the sinister promiscuity of so many bodies unknown to one another.“).

Futurists, a hundred years before, were to come share the historical reference point with the neofolk artists’ depiction of war and modernity, but from a different perspective. While the first openly glorifies violence, war and the world to come, neofolk scene varyingly mourns and celebrates the destruction of that world and the fall of nations. This complicated juxtaposition can be joyfully analogized with a quote from Alfred Jarry’s early modernist play Ubu in Chains: “We shall not have succeeded in demolishing anything unless we demolish the ruins as well. But the only way I can see of doing that is to use them to put up a lot of fine, well-designed buildings.” [10] While but the lyrics may condemn the world now long-gone, the audio-visual aesthetics are, in some sense, rebuilding it.

This essay most likely angered any and every neofolk fan and musician who read it, for its very much based on generalization through few bands. However, what those bands have created is, in my opinion, extraordinary piece of underground music. In the end, looking purely at the lyrics, one can barely distinguish them from indie or even pop songs. It is the masterfully crafted context, music and visuals, that these artists have managed to build that give the lyrics and the project as a whole very particular meanings. Furthermore, the ambiguity and the endless contradictions in the presentation of this music make it a very underappreciated genre of the 21st century. It is at the same time emotional and cold, serious commentary and restrained satire, as well as politically aware and historically conscious. Most importantly, it refuses to disclose its motives. In our times when social commentary and comedic presentation are losing subtlety, and when categorization of ideas and expression of values are increasingly demanded, the proudly enigmatic art of neofolk is well appreciated.

[1] Andrzej Bong, “Mini interview with Death in Rome.” Suru.it, 7.9.2015, https://www.suru.lt/mini-interview-with-death-in-rome/, accessed on May 11, 2019.

[2] Death in Rome, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCp-hYw-Lr5YpPfVcz33u8Hw

[3] Death in Rome, “Death in Rome – Diamonds (Rihanna – Cover)”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SE29Ic8Wxko

[4]Tenebrous Kate, “Strength Through Satire: The Neofolk Mischief of Death in Rome.” Black Ivory Tower, 25.9.2016,https://blackivorytower.com/2016/09/25/strength-through-satire-neofolk-mischief-death-in-rome/, accessed May 8, 2019.

[5] Eric Hobsbawm, “Introduction: Inventing Traditions,” in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 2.

[6] Eric Hobsbawm, “Introduction: Inventing Traditions,” 4.

[7] S. L. Weatherford, “This Light Shall Undress All: An Interview with Jerome Reuter of Rome + Exclusive Track Premiere.” Heathen Harvest, 23.3.2016, https://heathenharvest.org/2016/03/23/this-light-shall-undress-all-an-interview-with-jerome-reuter-of-rome-exclusive-track-premiere/, accessed May 8, 2019.

[8]Andrzej Bong, “Mini interview with Death in Rome.”

[9] Filippo Marinetti, The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism, translated by R.W. Flint. Source for translation: Umbro Apollonio, ed. Documents of 20th Century Art: Futurist Manifestos. translated by Brain, Robert, R.W. Flint, J.C. Higgitt, and Caroline Tisdall, (New York: Viking Press, 1973), 19-24.

[10] Alfred Jarry, “Ubu Enchained,” in The Ubu Plays: Includes: Ubu Rex; Ubu Cuckolded; Ubu Enchained, translated by Cyril Connelly and Simon Watson Taylor, (New York: Grove Press, 2007), 1.

Leave a comment